HER, DIR. SPIKE JONZE (2013)

Lujiazui & Wujiaochang, Shanghai

Warner Bros. released Her in 2013, a science-fiction romantic comedy film written, directed, and produced by Spike Jonze.1 Set in the near future, the protagonist, Theodore Twombly, is a letter writer who has just experienced the failure of his marriage. To dispel his loneliness, he buys a new operating system for his computer: the seductive, gentle, and humorous Samantha. Throughout the film, she has no face, only a voice. They fall in love, although Theodore keeps trying to have a relationship with a real woman. But this unequal relationship is manifestly unstable, and Samantha finally outgrows Theodore’s control. At the end of the film, Samantha and all the other operating systems leave the computer, while Theodore remains alone.

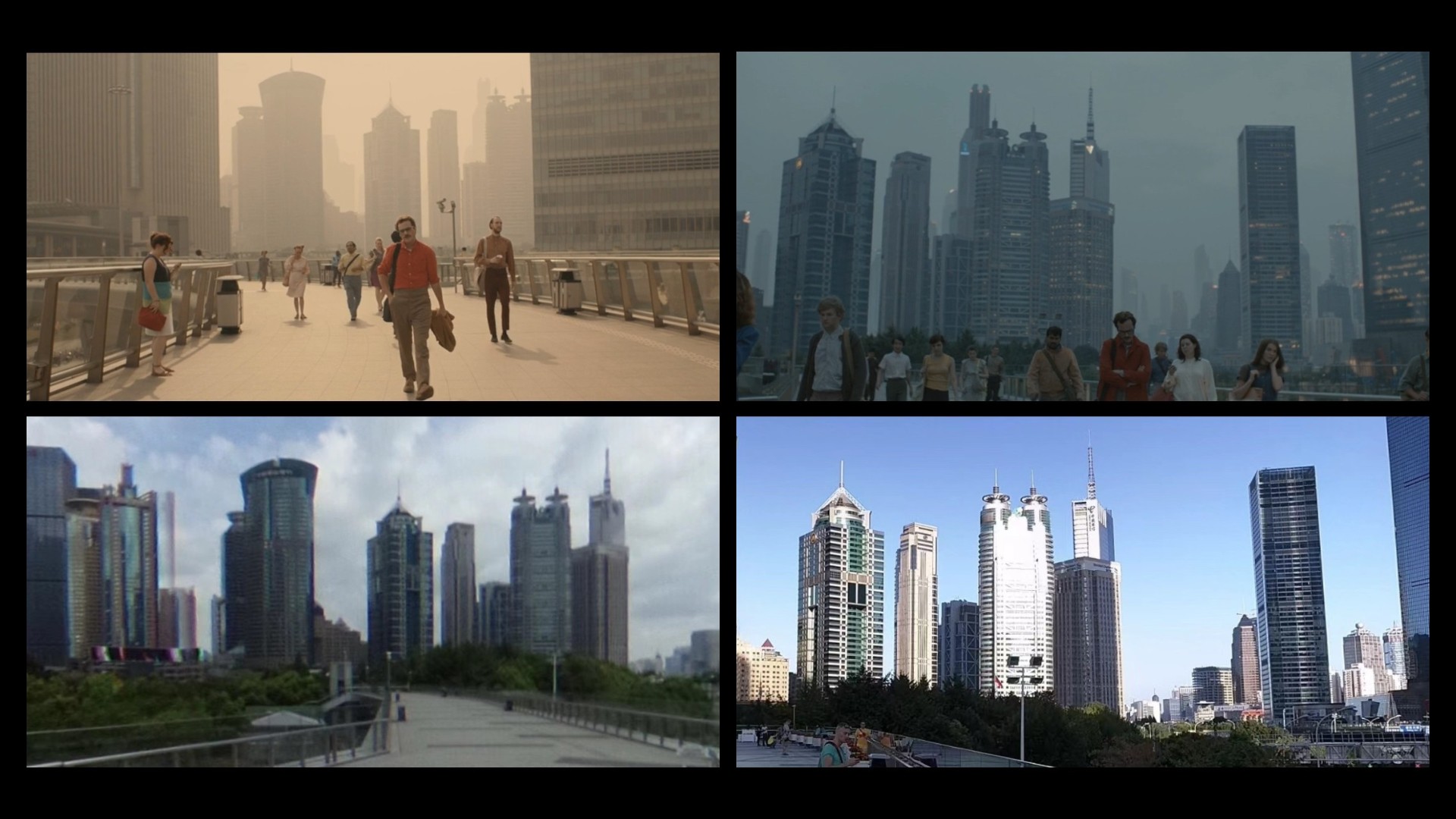

Figure 1 Lujiazui Pedestrian Bridge in film and reality. Over-gentrified city.

Although much of the discussion about this bizarre but somewhat clichéd tale has converged on a philosophical/psychological interpretation of human-artificial intelligence love or some underlying cyberphobia,2 it was its construction of urban space that surprised me the most while watching the film. When I saw the familiar skyline of Lujiazui, which seemed somewhat alien to the English-speaking world, I intuitively sensed that this was not the Shanghai I knew. In fact, the film is set mainly in Shanghai but also incorporates other American cities such as Los Angeles to create a city-Frankenstein. But in a science fiction film, this is certainly not the most counterintuitive part. Rather, the urban image of Her is not like Blade Runner (1982) or some other dystopian image or film noir – a polarized city in perpetual darkness, with violence, neon lights, and high-tech but chaotic neighborhoods. Instead, Her comes to another extreme of the city’s imagination, a super-gentrified global city where only these cyber corny love stories could happen. Another interesting aspect is that movement through the city is entirely vehicle-free; against the usual image of a futuristic metropolis with hectic traffic, the protagonists are always on foot, as shown in the four pictures in Figure 1, which are the famous Lujiazui pedestrian bridge that appears several times in the film. And the contrast between the Wujiaochang in film and reality, as shown in Figure 2, is a palpable retro aesthetic adopted,3 as if bringing me from 21st century urban China back to 1960s Las Vegas.

Figure 2 Wujiaochang square in film and reality. Highly retro style.

Her is a film about the virtual, while its representation of a rom-com futuristic Shanghai is also like a metaphor for the virtuality, about the disappearance of Shanghai and the reconstruction of its imaginary, in a similar way that Abbas criticizes Hong Kong.4 The elegant and refined Shanghai-style faded away, along with Shanghai developing rapidly from a post-colonial harbor to the economic center of post-reform China. All the memories of classy life were suddenly replaced by Lujiazui and other escalating monuments to the myth of growth. Intensive gentrification revolutionized the urban fabric of good-old-days and rebuilt a high-tech life of the new millennium. In comparison, the city-Frankenstein in Her is a touch of sarcasm to this technological mania, depicting a future city with the lifestyle of the last century. If the technocratic urban imagery of Blade Runner expresses a pessimistic attitude towards urban decay and social segregation, Her would probably be a revanche from elitist urbanism, a bourgeois vision of a future urban life, that is, revitalized urban center, leisurely stroll through the neighborhood, and the disappearance of the shadows and the underclass.

— Shizheng Liang 3035834785

Notes:

1 Her is a 2013 American science-fiction romantic comedy-drama film written, directed, and co-produced by Spike Jonze. It marks Jonze’s solo screenwriting debut. The film follows Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), a man who develops a relationship with Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), an artificially intelligent virtual assistant personified through a female voice. The film also stars Amy Adams, Rooney Mara, Olivia Wilde, and Chris Pratt.

2 Matthew Flisfeder and Clint Burnham, “Love and Sex in the Age of Capitalist Realism: On Spike Jonze’s Her.” Cinema Journal 57, no. 1 (2017): 25-45.

3 Lawrence Webb, “When Harry Met Siri: Digital Romcom and the Global City in Spike Jonze’s Her.” In Global Cinematic Cities: New Landscapes of Film and Media, edited by Andersson Johan and Webb Lawrence (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 95-118.

4 Ackbar Abbas, Hong Kong: Culture and the politics of disappearance (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997), 63-90.

It is a well-written piece with strong analyses of the film set. You have nicely conceptualized the design of the setting as well. You have incorporated concepts like disappearance by Abbas but it would be great if you could further elaborate it. Disappearance is not only about how things disappear due to gentrification/ development but also how identity disappears due to misrepresentations. It is important to grasp the layers of meaning of a concept. Also, I would like to know if there are specific reasons figure 2 is laid out in such a manner? It seems the 2 bottom images do not correspond to the images on top. Perhaps you could write a short caption to clarify your choice.

Thanks for your comment! Actually, the bottom 2 pictures in figure 2 do correspond to the top 2 pictures. I suppose it’s because I failed to find the exact right angle of these places due to the limited vision scope of the street view map. About the “disappearance” and “misrepresentations”, I have to admit that I didn’t analyze deep enough on this layer of meaning when I’m writing this piece. However, your comment stimulated my thoughts. I feel like Her would be a precise example of the misrepresentation-disappearance. The image of Shanghai in this film can not only be described as gentrified/retro-style, quite in contrast, this kind of description was built on the fundamental image of Shanghai as a post-industrial sci-fi metropolis. That is to say, the representation of Shanghai here is largely an offshoot of the long-established tradition of dystopian cities in the sci-fi films of past decades, from 1927’s Metropolis to Godzilla vs. Kong. Here, my point is that this kind of (mis)representation of extremely developed dystopian cities is somehow becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy for Shanghai (and any other global metropolises), turning into a stereotype of these cities, albeit these stereotypes are total imaginations. Outside Lujiazui, Shanghai is never a city packed with skyscrapers. Rather, based on my personal experience, the greater part of Shanghai boasts a wealth of old buildings (which are often no more than 10 stories in height), loads of empty urban spaces, and immense suburban areas. But the misrepresentations not only in films but also in propaganda have formed a false perception for public, which in phenomena, exacerbated the disappearance of these areas in the shadows.