SYNOPSIS:

The film narrates the dramatic changes in the life of typical triad gangster Moon, after his mentally deficient partner Lung handed him suicide letters taken from a victim Susan Hui. Together with kidney cancer patient Ping, lovers by chance with Moon, the trio attempts to deliver the letters as Susan’s spirit lingers in Moon’s flat. Moon, unable to donate a kidney and protect his friends in time, eventually loses both his friends, triggering him to take revenge on two triad bosses who have brought the trio misery, and committed suicide to join his friends in becoming, in Ping’s mothers’ words “eternally young.”, released from the fear reality and of the future.

Through Moon’s journey, an authentic Hong Kong commoner story, the film explored grassroot misadventures such as broken families and gang violence through the lens of the trio, and addressed the youngsters’ shared sentiments of disillusionment, helplessness and fear of the future, under the unique time context of the 1997 handover period.

SCRIPT:

MC = Matthew Chung Chi Yui, MW = Marcus Wong Tsun On

MC: Greetings, everyone. This is Matthew Chung Chi Yui, and with me is Marcus Wong Tsun On. Today we’ll be discussing the first film in Fruit Chan’s handover trilogy, 1997’s “Made in Hong Kong.”

MW: Through chronicling the journey of a juvenile triad gangster, Moon, who protected his mentally impaired friend Lung from bullying and fell in love with a triad debtor’s daughter, renal cancer patient Ping, the 1997 film explores the daily lives of 90’s Hong Kong youngsters. It addresses their shared sense of helplessness and disillusionment in the face of reality, common lower-class misadventures, as well as uncertainties of the post-handover future.

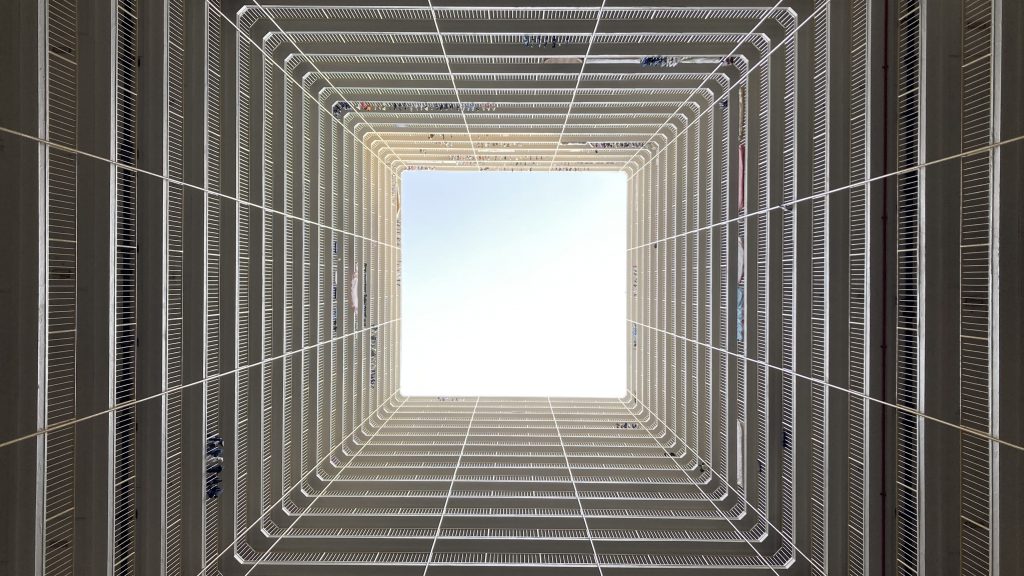

MC: To tell an authentic local story focusing on the lives of 90’s commoner youth, Chan used familiar daily life spaces as the set. One of these spaces is the atrium of a twin tower public housing building in Shun Lee Estate, Ping’s home. This ubiquitous commuting space seen in many public housing blocks was transformed through cinematic treatment to serve narrative needs and to echo themes of the film. Marcus, do you remember how this was done throughout the film?

MW: Of course. The atrium was first presented as an amphitheater-like, voyeuristic space. At the beginning of the film, when Moon arrived at Shun Lee Estate to collect debt from Ping’s family, another debt-collecting dispute had already broken out on the balcony outside Ping’s flat. To present the atrium as an amphitheater-like space, the film first sets up the balcony outside Ping’s home as the “stage” through differentiating the family’s flat with other apartments using red paint graffiti on the external walls, a form of intimidation used by local debt collectors when demanding debt repayment.

MC: Alongside this, the film then establishes Ping’s flat as the center of attention through a montage of static full shots of spectating tenants. Attracted by the ruckus echoing in the enclosed atrium, these voyeurs spectated across the open-air space from the balconies of different floors. The filmmakers utilized the echoing noise, visual differentiation and other tenants’ reaction to present the atrium as a theater, transforming this rather mundane commuting space. I recall our experience of the space wasn’t as dramatic right, Marcus?

MW: I’d even say it was worlds apart. As nobody was deferring debt payment, and there wasn’t an unexpected event taking place, not only was the atrium much quieter, but it was also much less populated as there is nothing attracting voyeurs to stay and spectate. Since these atrium balconies’ basic function is to serve as common walkways from the flats to the elevator lobby, most people pass through them quickly.

MC: We do occasionally see a few tenants leaning against the railings or doing the laundry, but without something to capture mass attention, these square ring balconies were more like commuting spaces rather than voyeuristic ones. I’m curious as to why the atrium was presented in such a way. Perhaps you can talk more about this, Marcus?

MW: Presenting the atrium as such could dramatize the financial troubles faced by Ping’s family, informing the audience that they are deep in debt. This not only provides an introduction of the two characters without words, but it also helps support the narrative by foreshadowing Ping’s families’ conflicts with their creditors in the film. This paved the way for the natural introduction of a pivotal character, Fat Chan, a creditor of the family who eventually causes Moon a devastating injury and the misery of Ping’s family. This also serves as the filmmakers’ social commentary of Hong Kong’s society, as the voyeurs watched apathetically, it resembles the commonly observed social phenomenon of local people acting as apathetic bystanders to protect themselves, even when they see someone in need.

MC: Apart from presenting the atrium as an amphitheater-like, voyeuristic space, the film depicts the atrium as a repetitive and endless space by leaving parts of the atrium off-screen. As the plot moves forward, Moon returns to the estate to collect more debt, or to meet Ping. In these scenes, the atrium balconies were presented to share the same features – the same gates, the same railings. The audience identifies this as an architectural pattern, and would then subconsciously imagine its continuation whenever it is visually suggested.

MW: To further present the building as endless, the filmmakers mainly avoided capturing the top opening of the atrium and the ground. Using these two methods simultaneously creates an illusion that makes the building seem as if it repeats itself forever. This way of presentation was reused throughout the film when the atrium was featured, no matter if it’s in a wide shot of the scene featuring Moon and his gang, or the medium close-up shots of Moon and Ping chatting beside the railings. I recall it was a little different from what we experienced, right Matthew?

MC: You’re right. Although the repetitive design of the public housing block presented in the film is identical to that in real life, the experience was different as the illusion of endlessness was broken. The omission of the atrium’s ground and top opening made the building appear to go on forever in the film, but in reality, the building at Shun Lee estate only has 23 stories. This made the opening of the atrium and the ground much more obvious, and as our sights fell on them easily, the building appeared much shorter than how it was presented in the film. But Marcus, what’s the point of making the public housing block feel repetitive and endless?

MW: This symbolizes the similarity between Hong Kong’s youngsters’ circumstances. The atrium is a familiar space to commoners as the many public housing blocks they live in in Hong Kong have similar, even identical designs. Its presentation as an endlessly repetitive space symbolizes the social phenomenon of many grassroot youngsters sharing similar daily lives – inhabiting similar living spaces and going through the same mishaps. Just as Moon said in the film, ‘People like me can be found all over the streets.’. The illusion serves as a visual symbol illustrating that, like the trio, these youngsters lived in public housing blocks, got raised in shattered families, experienced triad violence…

MC: Yep. Besides this, the depiction of the atrium as an endlessly repetitive space also points to the fact that these problems are ongoing and can hardly be solved. This architecturally repetitive feature of Hong Kong’s public housing blocks was used to symbolize the commonness of the trio’s circumstances, and how the related troubles are endlessly troubling youngsters, fulfilling the director’s wish to tell a familiar Hong Kong story while echoing with the theme of helplessness and powerlessness felt by youngsters in the face of reality.

MW: Besides presenting the atrium as an endlessly repetitive space, The Director also foregrounded railings to present the atrium as a confining, jail-like space. As the story progresses, Moon proposes to donating his kidney to Ping for a transplant during a chat. In this scene, a static, high-angle wide shot was used to present the atrium as a confining space. By deliberately framing the duo within the gap of 2 balusters of the railing in the foreground, on a balcony high above, the characters’ sizes are rapidly reduced, making them appear as if they were trapped between the balusters, presenting the atrium as a confining space.

MC: Also, when the movie filmed the duo in a series of low-angle panning close-ups, the camera reveals the imprisoning architectural characteristic of the atrium. As the 4 sides of flats enclosed the space, it blocked the surrounding city from the camera. More importantly, the shots across the atrium, such as the montage cuts and wide shots we’ve discussed, all foregrounded the railings, emphasizing their presence. All of these presentation techniques converge to establish the atrium as a Prison-esque space. Marcus, I remember the experience we had at Shun Lee Estate was more or less the same, right?

MW: Yup. The experience at the atrium was surprisingly similar. The only major difference I could recall is that when we tried to recreate the wide shot we discussed earlier, instead of standing and taking the shot at eye-level, we had to bend down and place the camera behind the railings. Except this, just as the film had presented, the design of the atrium does make the space feel confined.

MC: Yes, besides the 4 walls enclosing the atrium, the railings wrapping around the balconies would always obstruct our sightlines as we looked across the atrium. All these aligned with what we saw in the film. Marcus, do you have any ideas as to why the filmmakers decided to present this living space, a supposedly homely space, as a prison?

MW: By presenting it this way, the inhumanness of Hong Kong’s public housing architecture is revealed. Ironically, this familiar jail-like design offers a fitting backdrop that is both “Made in Hong Kong” and consistent with the theme.

MC: Another purpose of this is to echo the film’s theme of youth helplessness and powerlessness. As we have discovered, the shot filming Moon and Ping between the 2 balusters could only be achieved if the camera’s position was intentionally lowered, hinting at the fact that the filmmaker had the intention to convey a message. This intention can also be observed as he shrunk the duo to make them appear powerless. Marcus, perhaps you could talk about how this connects with the rest of the movie?

MW: Sure, besides this shot and the scenes taking place at the atrium, other scenes of the film also intentionally foreground the confining infrastructure like railings and nets, such as the scene at the school and the hospital. This consistent way of presenting the sets of the film was done to visually represent the film’s theme of youngsters’ sense of helplessness and powerlessness, as they lack the ability to escape the cage of circumstances confining them.

MC: As Chan said in an interview, he “tried his best to use those housing estates that are unique to Hong Kong to highlight its image, which is a uniqueness that is the whole spirit of “Made in Hong Kong”” (Chan, as cited in Cheung, p.79, 2009). Through presenting the atrium of Shun Lee Estate’s twin-tower public housing building in filmic ways, this essential part of HongKongers’ collective memory was transformed into a fascinating stage for this authentic local story.

MC: Thank you everyone for listening to this podcast and we wish you a nice day. Goodbye!

MW: Bye!

Chung Chi Yui Matthew (UID 3036002808) and Wong Tsun On Marcus (UID 3036002676)

References:

- Cheung, E. M. K. (2009). Fruit Chan’s Made in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press.

Nice work! The podcast had very comprehensive analysis and you evaluated the depiction of Shun Lee Estate thoroughly. I enjoyed your close reading of the spatial quality of the atrium and how different architectural elements are portrayed with the use of cinematography, and how they serve the ideas of class social issues in the film. The interpretation of the atrium as a vouyeuristic space is interesting and you have demonstrated the argument well. I appreciated your observations from visiting the site that the opening and ground of the building being omitted in the film which creates a sense of endlessness to these stacked floors. The podcast has a clear structure and has a conversational quality, and as an audience it is easy to follow your narration.