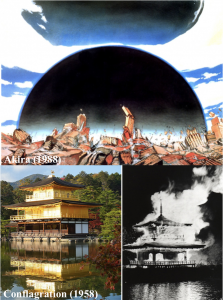

While commonly understood by general audiences as a straightforward derivative of humiliation and lingering traumas from the second world war, Japanese apocalyptic imagination comprises sub-genres more than the cliched detonations of fission bombs by ill-natured men: which span across natural disasters and extraterrestrial invasions. The fictional narratives have tapped into more than the nuclear anxiety of shuddered ground and radioactive remnants. This archipelago nation in Sinking Japan (1954) was entirely submerged by the eruption of the dormant Fuji, while in Akira (1988) it unveiled a vision of a “neo” Tokyo, where supernatural power Akira restored the order in the post-apocalypse dystopian capital. The awakening of the prehistoric monster Godzilla in the thirty-five films it starred in allowed audiences to predict another extirpation in a new locale of the new productions. With this range of different movies, Japanese fantasies of destruction have long been versified in the society as a poetic embracement of Japanese culture and history.

It still is, however, a categorical truth that the two polluted lacerations from Hiroshima and Nagasaki engraved wounds on Japanese’ minds that may take longer than the half-life of carbon to heal. A wound that is inflicted by another human is generally deeper and more incise than accidental abrasions because such wound is intentional. As Hiroshima and Nagasaki detonations were purposefully conducted by another country, the pain would undoubtedly be greater than the recent Fukushima nuclear accident. Considering that production is newly introduced biannually either in Toho or Hollywood, the Godzilla franchise serves as a constant reminder for Japanese of their ‘ethnic humiliation’ undergone in the last century. Many scholars support this notion: Susan Napier critiques Godzilla as a reimagination of Japanese’s tragic wartime experiences, and William Tsutsui argues that it allowed the reconstruction of ideology and faith. Meanwhile, the world-renowned One Punch Man animation series takes the radioactive wound to the next degree: every episode begins with a new total annihilation of the city Z. The metropolis is flattened without a trace when new villain-of-the-day is introduced. Such a normalization of the psychological unbearable emerges (i.e., commonplace nuclear destruction) in post-war Japanese pop culture.

It still is, however, a categorical truth that the two polluted lacerations from Hiroshima and Nagasaki engraved wounds on Japanese’ minds that may take longer than the half-life of carbon to heal. A wound that is inflicted by another human is generally deeper and more incise than accidental abrasions because such wound is intentional. As Hiroshima and Nagasaki detonations were purposefully conducted by another country, the pain would undoubtedly be greater than the recent Fukushima nuclear accident. Considering that production is newly introduced biannually either in Toho or Hollywood, the Godzilla franchise serves as a constant reminder for Japanese of their ‘ethnic humiliation’ undergone in the last century. Many scholars support this notion: Susan Napier critiques Godzilla as a reimagination of Japanese’s tragic wartime experiences, and William Tsutsui argues that it allowed the reconstruction of ideology and faith. Meanwhile, the world-renowned One Punch Man animation series takes the radioactive wound to the next degree: every episode begins with a new total annihilation of the city Z. The metropolis is flattened without a trace when new villain-of-the-day is introduced. Such a normalization of the psychological unbearable emerges (i.e., commonplace nuclear destruction) in post-war Japanese pop culture.

Some critics view the secure-horror films as both a celebration of visual annihilation and revitalization of faith. This shaded visions of total annihilation of culture and monuments are also evident in modern Japanese literature, as Kinkaku-ji (The Temple of the Golden Pavilion 金阁寺) by Mishima Yukio was based on the 1950 arson that shocked the Japanese public. An acolyte was so indulged in his imaginary visions of the monument’s beauty in which he became convinced with destroying the temple to preserve its beauty. Having been tasting the bitter aftermath of the second world war, the wooden Kinkaku-ji in flames witnessed the death of nihilism and rebirth of new nationalism: indulgence in the nihilistic, sometimes self-contradicting philosophies of guilt and self-reflection are overtaken by the destructive obliteration and hope for a new future.

Today, Japan is welcoming the new Reiwa era, and is seemingly no longer haunted by shadows of its past. However, nothing beats the destruction of Japanese cities as awakening calls for society. Japan may always be in the juxtaposition of imminent threats of destruction and reactionary yearnings for growth.

‘Oh no, there goes Tokyo, but it will be back and better than ever before.’

By Dong Yuqi Kiki (3035447879)