Ghost in the Shell (1995)

In his article “Technology and (Chinese) Ethnicity”, Darrell William Davis asks this question: why has Chinatown become an essential visual motif for dystopic future in cyberpunk classics such as Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell (1995)?

A simple (yet valid) explanation would be Orientalism, or the use of the East as a signifier of “other”. To represent the mysterious and unknown future, a future that seems so “alien” to us, films have to employ the visual strategy of “otherness” to create a defamiliarizing effect. This otherness could be gendered, as there are often female cyborgs or robots in sci-fi films (Racheal in Blade Runner and Kusanagi in Ghost in the Shell ). The otherness could also be ethnic, as exemplified by the presence of Chinatown: “Chinatown is coded as something other” (148). Such utilization of otherness certainly involves “colonial thinking”(137) as Chinatown is often merely a background for “jaded white heroes”(138) to act.

However, the reading further leads us to notice that Chinatown is not China. While China might be some exotic country far away, Chinatown is definitely an internal component of the urban landscape in the West. This means that Chinatown is “neither China nor (our) town, doggedly following its own course, known only to its denizens” (148), an internal “other” rather than an external one. Darrell William Davis points out that Chinatown is (for westerners) both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time, which is precisely how a human being would feel about a cyborg. A cyborg is like human but not human, “recognizably human” (148) but “withheld, intractable, marked off” (148).

In the reading, Darrell William Davis also analyzes specifically why Hong Kong is chosen as an architectural archetype for Ghost in the Shell (and many cyberpunk films that come after). An information city is hard to visualize unless it is a consumerist city full of signage (like Hong Kong), where “signs are externalized”(142) and information is foregrounded. Therefore, Hong Kong inspires the visual design of an informational space. Nonetheless, I would like to argue that what Darrell William Davis neglects, or fails to acknowledge, is the “class unconscious” of cyberpunk sci-fi that links this genre to Hong Kong. In cyberpunk works, the future society is always depicted as a society of drastic social division and class stratification. I call this the “class unconscious” of cyberpunk because the issue of class is not directly dealt with in most works; however, it remains an important factor in the spatial and narrative setting. Hong Kong, with its juxtaposition of fancy skyscrapers and decaying residential buildings, is a capitalist urban space that inscribes the words “class division” on its forehead. This is another reason why Hong Kong becomes a prototype for the architectural imagination of cyberpunk.

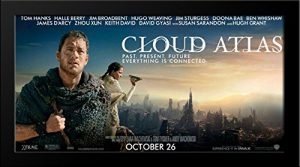

Blackness in Cloud Atlas

For Hollywood sci-fi films, the ethnic “other” needed for the representation of technological and futuristic “other” is certainly not limited to Chinese or Asian. There are several “alternatives, such as Jewish, Hispanic, or African American” (138). For example, in Cloud Atlas, the jaded white hero (Tom Hanks) who has fallen to the primitive state (because of some catastrophe) is aided by a black female (Halle Berry) who comes from a much more advanced civilization. In Alita: Battle Angel, the “iron city” where the narrative unfolds is visually a combination of Latin-American cities: Havana, Rio and Mexico City. As the population of Hispanic immigrants continues to grow in the US, we may expect to see more Latin-American elements filling the position of “other” in forthcoming Hollywood sci-fi films.

Iron City in Alita

BY Jimmy Zhu Jieming (3035448524)